Author: Aleksandra Vuletić

This working paper was first time published in 2012 at Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (link to PDF). It is presented here thanks to the courtesy of the author. © Copyright is held by the author.

Introduction

The structure of the Serbian family and household has been the subject of discussion and study for a long time, with a particular focus on the complex family household, often labelled zadruga. A considerable part of this literature, especially the literature of older date, is based on ethnographic material. Apart from being a subject of ethnographic description, zadruga has been the subject of many sociological, legal and economic analyses. Quantitative studies of the household structure based on census microdata are more recent. Even though there is a considerable amount of preserved census material which is nowadays kept in one place, this material has still not been used much for research purposes.

Census microdata were first processed in the second half of the 19th century by employees of the National Statistics Office. These census tabulations are still one of the main sources of information on population characteristics in social history research. Since the 1960s there has been a growing interest for the preserved census microdata, primarily for those of the 1862/63 census which is preserved for the majority of districts. The data have been used mostly by researchers interested in local history and genealogy. This interest has resulted in extensive printing of the 1862/63 census microdata. To date, approximately 30% of this material has been published. One part of the material was edited by professional historians, while the rest was printed by various local publishers, owing to the enthusiasm of amateur historians.

Joel M. Halpern was one of the first scholars who used 19th century microdata in his studies (Halpern 1958, 1972, 1981/82, 1984). Halpern’s database, which contains census material from 1863 and 1884 for eight villages in central Serbia, is now kept at the Centre for Southeast European History at the Karl-Franzens University of Graz. It has been used by researchers from this Centre, like Karl Kaser (Kaser 1994, 1995) and Siegfried Gruber (Gruber 1999, 2011, 2012). The 1862/63 census microdata appeared also in papers of Michael Palairet (Palairet 1995). Apart from 19th century censuses, medieval sources and Ottoman censuses were used for the quantitative analysis of family structure (Hammel 1972, 1976).

In Serbian scholarship, census microdata were occasionally used in research papers, mainly in ethnological studies of the family (Stojančević 1995). The quantitative investigation of census and census-like materials intensified in the previous decade. Gordana Kaćanski studied the family structure of ten villages using the 1832 tax lists (Kaćanski 2001). Aleksandra Vuletić conducted a research on the household structure and kinship composition on the basis of microdata for 13 districts from the 1862/63 census (Vuletić 2002, 2003). Bojana Miljković-Katić extensively studied urban microdata from the same census (Katić 1986, 1988, 1990, 1991, 1994; Miljković-Katić 2002), as well as the 1834 census microdata in one research paper (MiljkovićKatić 2003). B. Đurđev, T. Lukić and M. Cvetanović analysed microdata from the 1862/63 census for one district (Đurđev, Lukić, Cvetanović 2012). Future studies should focus on comparing data from all preserved censuses.

Historical background

At the beginning of the 1800s Serbia had been a part of the Ottoman Empire for centuries. The two uprisings against the Ottoman rule (1804–1815) marked the beginning of the liberation process and the establishment of a nation state. The status of autonomy that Serbia had unofficially enjoyed since 1816, was officially recognised by the Porte in 1830. Serbia was granted the status of a vassal principality within the Ottoman Empire with broad autonomy in administering its internal affairs. In 1878 it gained full independence at the Congress of Berlin. Four years later the principality was raised to the level of the kingdom. Serbian borders were changed twice in the 19th century. In 1833 its territory was enlarged with the addition of six counties liberated by rebels during the First Uprising. In 1878 it gained four counties in the southeast which it had previously conquered in the wars with the Ottoman Empire.

*

One of the most important elements of Serbian autonomy was the permission given to Serbian authorities to collect taxes themselves. The first population registers, created for tax collection purposes, date back to 1815. With the official recognition of Serbian autonomy in 1830 and the enlargement of its territory in 1833, there was a growing need for registration of the entire population. Consequently, the first census was conducted in the following year – 1834. The total population count was not only a result of practical needs of the new state administration, but also an outcome of its aspiration to model itself after developed European countries to the highest possible degree. Prince Miloš thus pointed out while announcing the first census: “The census has to be taken in order to determine both the population total and its wealth, as it is determined in civilised countries” (cited in: Cvijetić 1984: 10). Two years later compulsory registration of vital data was introduced, which was to provide a more profound insight into the population. Although vital registration was in the hands of ecclesiastical authorities, it was the state that initiated its establishment.

Sources for population reconstruction and family reconstitution

Tax lists

Tax lists are one of the major sources of information on population characteristics for the first half of the 19th century. The Archives of Serbia keeps about 900 various tax lists dating back to the 1816–1843 period. Most of the lists originate from the 1830–1839 period. Among them, approx. 250 were made for the purpose of collecting the two main taxes – “harač”, paid by all men aged 7 to 80, and “glavnica”, paid by all married men. Such lists, containing information about the marital status of enumerated males, shed some light on the family structure of that period.

Registers of vital data

The first mentions of registers of vital data date back to 1816, while keeping them became mandatory in 1836. Unlike the preserved tax lists and census lists that are all kept in one place nowadays – the Archives of Serbia, the preserved registers of vital data are owned by local archives. Their retrieval to churches where they once belonged has recently been initiated. Prior to retrieval, registers were microfilmed for research purposes.

Censuses

In the 1834–1910 period, 16 censuses were taken in Serbia: in 1834, 1841, 1843, 1846, 1850, 1854, 1859, 1862/63, 1866, 1874, 1884, 1890, 1895, 1900, 1905 and 1910. In 1879 a census was also taken in four counties which had become a part of Serbia in 1878. [1]

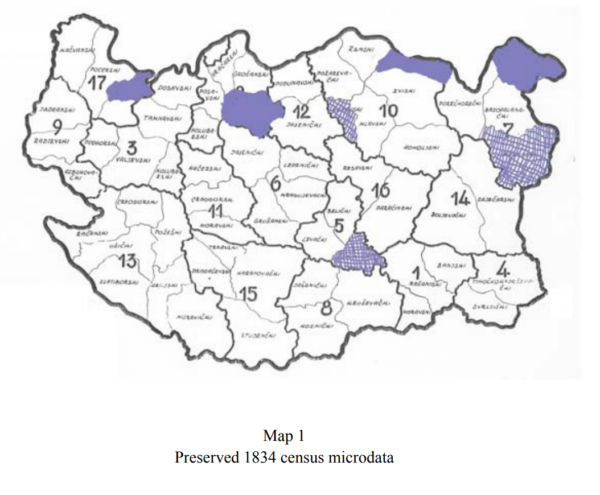

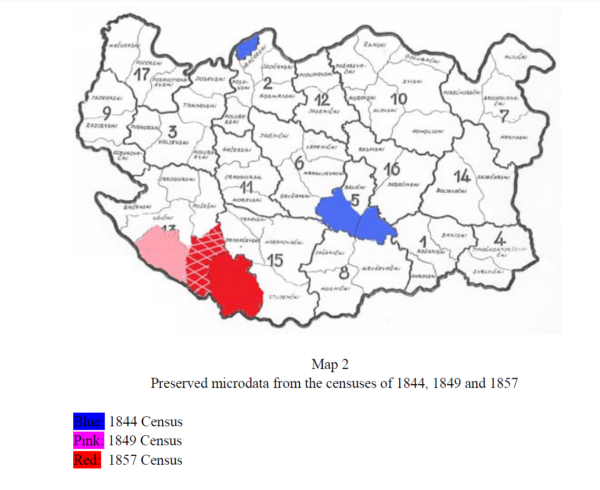

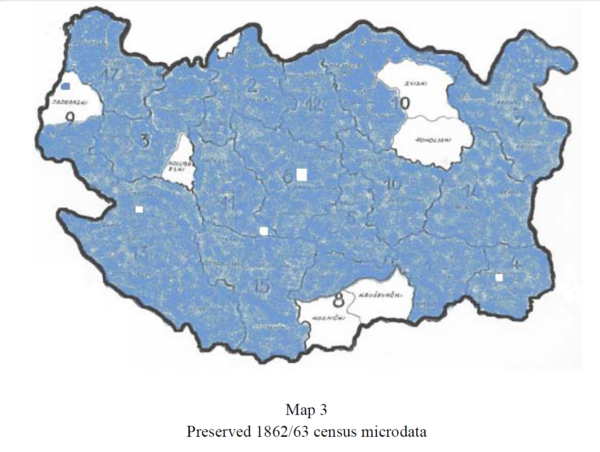

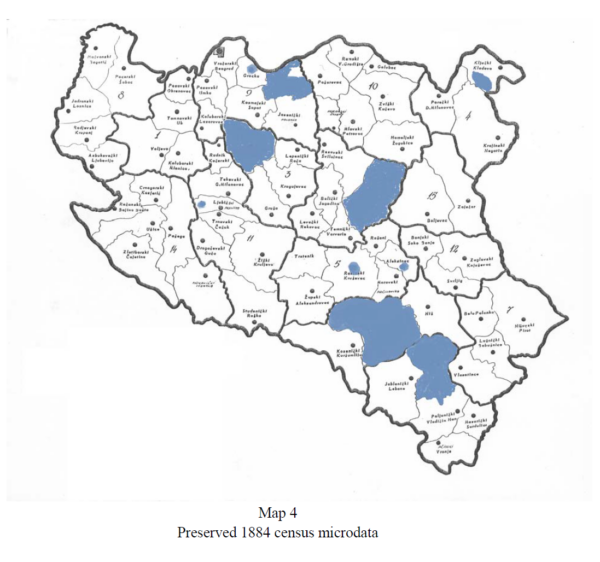

The censuses for which microdata have survived are those taken in 1834, 1862/63 and 1884. The 1834 census lists for seven out of total 61 districts have been preserved. The census preserved to the highest degree is the census of 1862/63 – microdata for 54 out of 61 districts have remained. From the 1884 census, lists for 11 out of 81 districts have been preserved. Apart from the above, several census lists from 1844, 1849 and 1857 have survived as well. The years when they were made do not correspond to the years when censuses were officially performed, so it is believed that these lists were created later because censuses were taken later in some districts or had to be repeated for some reason.

All preserved census lists, in the form of books, are kept today at the Archives of Serbia.

Organisation of statistics

In the 19th century an efficient state administration implied the existence of statistical offices which conducted the collection and analysis of a large number of demographic data. The establishment and development of such an office in Serbia was mostly due to one person, Vladimir Jakšić (1824–1899). He studied cameral sciences at the Universities of Tübingen and Heidelberg at the time when the “enthusiasm for statistics” was at its peak (Porter, 1988: 27). He took a special interest in statistics while listening to lectures of Johannes Fallati, a leading academic statistician in Germany at the time. While working as a civil servant in the Ministry of Finance, then as a professor at the Liceum and, finally, as head of the National Statistics Office, Jakšić firmly believed statistics to be essential for practical administration and state modernisation (“Glasnik SUD“ 71: 318–321).

In 1851 the first extract from one population census (1846) appeared in the publication called “Glasnik DSS”. Extracts from the consecutive censuses of 1850 and 1854 appeared in the consequent volumes of “Glasnik DSS”. These first census summaries were rather meagre. The publishing of extensive census extracts started with the 1866 census. In 1850 Jakšić proposed to relevant authorities the establishment of a statistical office, but this suggestion was not accepted until 1862, when the National Statistics Office was set up within the Ministry of Finance. Jakšić was appointed head of the Office. At the time, his personnel consisted of only two civil servants. The following year, in 1863, the Office initiated the publication of the statistical edition titled “Državopis Srbije”.[2] Until 1894 twenty volumes of this series, containing various statistical data, were released. The publication of statistical material continued within the new edition “Statistika Kraljevine Srbije” – the first volume was published in 1892. As census lists were not preserved for most of the censuses, these publications are the only source of census information. [3]

Jakšić tried to keep up with the current trends in European statistics. He therefore participated in many international statistical congresses (1857 in Vienna, 1863 in Berlin, 1867 in Florence, 1869 in the Hague, 1872 in St. Petersburg, 1876 in Pest, etc.).[4] The National Statistics Office was a member of the International Statistical Institute since its foundation in 1885. After Jakšić’s retirement in 1888, endeavours in the statistical domain were continued and further developed by Bogoljub Jovanović.

During the larger part of the 19th century, censuses were conducted according to rules and instructions issued by the central administration just before the start of census-taking. In the last two decades of the 19th century the domain of census-taking got its legal form. The first law on population and property census was passed in 1884, along with the law on tax reform. The next law on census was passed in 1890 (the Law on Population and Livestock Census), and it was partly modified and amended in 1900. This law finally regulated the procedure of census-taking. It prescribed that censuses should be taken every five years on 31 December. A census was to be carried out by municipalities which hired census takers – educated citizens (mostly civil servants, teachers and clergymen) for the purpose. On the central level, the National Statistics Office was responsible for coordination and supervision of the census process. The Minister of Economy was responsible for issuing of detailed rules and instructions for every census [5].

In the early 20th century, Serbia had a long tradition of population census-taking and a legally regulated census procedure. However, censuses were still accompanied by numerous weaknesses. The statistical department staff complained that legal regulations and rules could not be always complied with in the field. As constant problems that they encountered in each census they specified: the lack of trained census enumerators, inadequate care of local authorities about the implementation of a census, insufficient funds and the citizens’ lack of trust in every statistical action. [6] All this negatively affected the accuracy of data obtained in censuses.

Some features of census-taking

Despite a number of censuses taken during the 19th century, their history is not yet written. Apart from the study of L. Cvijetić which gives valuable information on the 1834 census (Cvijetić 1984), most information about census-taking is still derived from the 19th century series of “Državopis Srbije”. How and to what extent a considerable amount of gathered data was used in the state administration system is yet to be researched.

During the larger part of the 19th century censuses were taken in uneven intervals. The census process itself was not performed at the same time in all districts. It could last for months and, in some cases, for more than a year. The first census performed simultaneously in the whole territory of Serbia was the 1866 census. The Law on Census-Taking of 1890 finally regulated the intervals between two censuses – five years, as well as the precise time when censuses would be performed thereafter – 31 December.

Census forms were to be filled in by census enumerators throughout most censuses. The main reason was a high degree of illiteracy, especially of the rural population. Only at the beginning of the 1900s a part of the urban population was regarded to be able to complete the forms themselves.

The number and content of census entries changed in time. The name and surname, age and marital status were regular inquires in all censuses. For the first seven censuses, enumerators recorded only the names of males, while the female population was registered as a total within a household. Female names were recorded for the first time in the 1862/63 census. Starting with this census, registering of the female population by name became regular practice. The inquires related to taxation were regular up to the census of 1884, when they were omitted for the first time. Of all the census forms which have been preserved, only the form of the 1844 census does not contain the entry for occupation. The state of health was registered in a special entry or, if there was not one, in the last entry labelled “remarks”. Literacy, nationality and citizenship were not registered until 1866, when they became regular inquires. Questions about the denomination and country of birth were introduced in 1874. The eligibility for military service was the question asked only in the first census of 1834.

Up to the 1866 census, the population was registered by the permanent place of residence. In 1866 people were registered by the place they found themselves at the moment of census. Although this principle of the population count, based on the place of enumeration, was considered to be more in convergence with the modern principles of census-taking, it was abandoned in the subsequent two censuses. In the 1890 census both categories of population – permanent and effective, were introduced.

The Turkish population, which lived in towns up to 1862, was never registered.[7] The first three censuses did not include the Roma population either as most of them did not have conventional housing and their tax liability was different from taxes paid by the rest of the population. In the fourth census, in 1846, the entire Roma population was registered for the first time, but in the following census they were omitted again. From 1854 the Roma who permanently inhabited an area started paying the same taxes as the rest of the population, and were included in censuses from then on. In 1866, all Roma people, regardless of whether they had a permanent place of residence or not, were finally included in censuses.

Information on property was collected along with the population census on three occasions – in 1834, 1862 and 1884. While in 1834 and 1862 population and property information was recorded within the same census form, in 1884 these forms were separated. In all three cases the reason for property registration was the intended tax system reform which would allow taxation according to wealth, and not per capita. The first two attempts at conducting the reform were doomed to failure, so it was successfully conducted only in 1884. It has not been studied yet to what degree the property data obtained by the 1884 census were used in taxation.

Apart from the population censuses, livestock and agricultural censuses were conducted as well. The livestock fund was registered for the first time in 1859, then in 1866. Its registration became regular practice from 1890. Agricultural censuses were performed in 1867, 1889, 1893 and 1897.

The census of 1834

The first Serbian census asked the name of every male person in the household, their age, marital and family status, profession, military capability, real estate and tax liability. As for females, the census asked their number within each household. According to profession, the population was divided into six categories: priests, civil servants, other officials, merchants, artisans and peasants. Military capability was recorded in five columns: apart from the military capable, the incapable population was divided by age (1–7 and 7–18), physical disability and legal exemption from military service. Property information for every household encompassed these categories: ownership/non-ownership of a house, the size of cultivated fields, meadows and vineyards, as well as the number of plum trees. According to tax liability, the population was divided into those paying “harač” (all males aged 7–80) and “glavnica” (married men), and those not obliged to pay these taxes. The last entry “remarks” was intended for additional information, like the health and material condition. This information was mostly related to the ability of enumerated persons to pay taxes and to serve in the military.

Apart from the need to get a general insight into the population for the first time, the main, practical goal of the census was to gain an overview of the taxable and conscriptable population. The preparations for the census were made in the first half of 1834 and census-taking started in June the same year. At the time of census-taking, Serbia was divided into 15 counties with 61 districts called “kapetanija” (“kapetanija” was termed “srez” the following year). Only the inhabitants of Užice were not included in the census due to the unfavourable political situation in that town.

The central state administration, with the head office in Kragujevac at the time, was in charge of conducting the census on the central level. The printed census sheets with 29 inquires were sent to all districts since they were administrative units within which censuses were performed in settlements. Each district formed a census protocol based on these sheets.

The process of organising census material was decentralised. The districts were obliged to create summaries of all taken data by settlements for their territories except for the age of registered persons. Those summarised surveys were at the end of census protocols. The protocols were then sent to Kragujevac where the overall census survey was made. This survey remained unknown to the research community until 1984, when it was discovered in the Archives of Serbia, within the Fund of the Ministry of Finance. [8]

The final goal of the property census performed on this occasion was to enable the introduction of a tax system based on property value. Even though property data were collected, the state administration, which was being formed at the time, could not put the proclaimed policy into practice.

1834 Census form: families/with houses/without houses; name and surname (males only); age; marital status/married/unmarried or widowed; occupation/priests/civil servants/other officials /merchants/artisans/peasants; population total (males only); military service/capable/incapable because of/underage/1–7 years/7–18 years/physically disabled/legally exempt; incapable, sum total; property/farmland/meadows/vineyards/plum trees; paying /”arač”/“glavnica“; females, total (within each family); remarks.

Published aggregate data: Leposava Cvijetić, “Popis stanovništva i imovine u Srbiji 1834. godine“, Mešovita gradja (Miscellanea) XIII (1984), 9–118.

Preserved 1834 census microdata

County, district

Jagodinski okrug, Temnićka kapetanija: 38 villages (out of 64), 2061 households.

Krajinski okrug, Krajinska kapetanija: 26 villages (out of 47), 2347 households.

Krajinski okrug, Ključka kapetanija: 21 villages, 1288 households.

Požarevački okrug, Pečka kapetanija: 20 villages, 1321 households.

Šabački okrug, Posavska kapetanija: 35 villages, 1319 households.

Beogradski okrug, Turijska kapetanija: 21 villages, 880 households.

Požarevački okrug, Moravska kapetanija: 24 villages (out of 49), 1254 households.

Censuses of 1841-1859

In 1841, seven years after the first census, the second one was carried out. Although there was no law regulating census-taking, during the 1840s and 1850s censuses were conducted in almost even intervals: in 1841, 1843, 1846, 1850, 1854 and 1859. Despite this, little is known about these censuses in historiography. Extracts from 1841 and 1843 censuses have not been preserved, while the extracts from the following censuses – those of 1846, 1850 and 1854 are rather meagre. A bit more information is provided in the extract from the census of 1859.

Only several census lists have remained from this period. They are dated in 1844, 1849 and 1857.[9] None of these years corresponds to the above census years. Apart from the possibility that dating may be wrong, many convincing reasons for the chronological discrepancy could be suggested: at that time the census process often lasted rather long; it was not always conducted simultaneously in all districts; sometimes it was interrupted due to some unexpected circumstances and later resumed.

The preserved census forms suggest that these censuses were not as detailed as the first one, since they did not register property or eligibility for military service. They contained information on the name, surname, age, marital status, family relations within the household and tax liability of the male population. As in the first census of 1834, they registered only the number of females within a household. Unlike the census lists from 1844, lists from 1849 and 1857 provide information on the profession of enumerated males. They also introduced inquires about the temporary present and temporary absent population, including the information on the place/country of origin/migration.

Some sparse information on censuses taken in the 1841–1859 period could be found in statistical publications about censuses conducted in the subsequent period. This information relates mainly to the reliability of the previously taken censuses. Thus, the census conducted in 1841 was believed to be flawed since the population of Belgrade was not registered for some reason. The census of 1843 was considered less reliable than the previous two censuses since it was performed by a new team of civil servants who were regarded less competent for this job than their predecessors. The census of 1846 was considered reliable. In the census of 1850 the population of Belgrade was not counted well again. The next two censuses, those of 1854 and 1859, were considered reliable.[10]

1844 Census form: household (family) number; name and surname (males only); age; married/unmarried; tax paying/not paying; paying smaller taxes/civil servants/not paying; females (their number within each family); population total; remarks.

1849 and 1857 Census form: household (family) number; name and surname (males only);

occupation; age; married/unmarried; tax paying/not paying/paying property taxes/not paying

property taxes; females (their number within each family); not present/in some other parts of

Serbia/in the Ottoman Empire/in other countries; population total; foreigners/from other parts of

Serbia/from the Ottoman Empire/from other countries; foreigners, total sum; payers of the tax on

unmarried men; remarks.

Published aggregate data:

1846 Census: Jovan Gavrilović, “Prilog za geografiju i statistiku Srbije. Glavni izvod popisa Srbije u godini 1846”, Glasnik DSS III (1851), pp. 186–190.

1850 Census: Jovan Gavrilović, “Prilog za geografiju i statistiku Srbije. Glavni izvod popisa Srbije u godini 1850”, Glasnik DSS IV (1852), pp. 227–248.

1854 Census: Jovan Gavrilović, “Glavni izvod popisa u Srbiji godine 1854/55”, Glasnik DSS IX (1857), pp. 224–226.

1859 Census: „Izvestije podnešeno g. Ministru Finansije o čislu žitelja Srbije u godini

1859“, Državopis Srbije I (1863), pp. 86–97.

Preserved census microdata:

Census lists from 1844

County, district

Jagodinski okrug, Temnićki srez: 15 villages (out of 41), 747 households.

Jagodinski okrug, Levački srez: 23 villages, 732 households.

City of Belgrade: incomplete, 861 households.

Census lists from 1849

Užički okrug, Rujanski srez: 32 villages, 1764 households.

Census lists from 1857

Užički okrug, Ariljski srez: 35 villages, 2188 households.

Užički okrug, Moravički srez: 31 villages, 1998 households.

The census of 1862/63

The census of 1862/63 was performed in order to introduce a new tax system which prescribed taxation based on wealth. Therefore, more attention was paid to the property census and income estimate than to population count. Even though recording of property and income estimate had the primary role in the process of planning and conducting this census, it was the first census in Serbia in which the entire female population was registered by name. Registering of female population became regular practice in all subsequent censuses.

The census form asked information on the name and surname of all household members, their kinship relation to the head of the household, marital status, occupation, health condition and age. Thereafter, enumerated persons were to give detailed information about their property – houses and other buildings, cultivated fields, meadows, orchards, vineyards, forests, pastures etc. Census enumerators had the obligation to provide a financial assessment of recorded real estate, as well as to estimate the monthly income of a household. On the basis of these estimates, the head of a household was placed into two tax categories, one according to property, and the other according to income. Both categories consisted of seven tax classes.

The population census started in the spring of 1862, but was soon interrupted due to the political crisis over a conflict with the Turks and the subsequently introduced state of war. The census continued the following year, in 1863, when most of the population was registered. In the towns of Negotin and Kruševac it was completed only in 1864.

The property census and the announcement of a new tax law were not met with the warmest reception by people. A considerable number tried to represent their property and income smaller than they actually were. In the words of the historian Slobodan Jovanović, “The one having more than a hundred swine, declared twenty, the other having twenty, declared none” (Jovanović 1923: 179). Census enumerators, hired by municipalities, were ready to overlook such underestimations since they were likewise not interested in the accurate registration of property and the introduction of a new tax system. A doubt about the accuracy of the obtained property data was expressed immediately after the census. As a consequence, the new law never came into force.

Despite the controversies it provoked and although the collected property data were regarded useless, the census of 1862/63 survived to the highest degree. Preserved are 84 census books containing microdata for 18 towns and 54 districts. The census books for Belgrade are among the missing ones. A considerable number of census books have been printed in the last decades.

1862/63 Census form: ordinal number; name and surname of the male head of family, the female head of family, children, parents and other relatives and inmates not subjected to individual taxes and their occupation; health condition, i.e. whether he/she is incapable of working and for what reason; age/males, females; fixed assets/houses, land, other buildings and their financial assessment (in “dukats”); monthly income (in “talirs”); tax classification/according to property, from class 1 to class 7/according to income, from class 1 to class 7.

Published aggregate data: “Popis ljudstva Srbije u godini 1863“, Državopis Srbije II (1865), 12–17.

Preserved 1862/63 census microdata

Counties

Aleksinački:

Town: Aleksinac, 1125 households. Districts: Ražanjski, 50 villages, 2855 households; Banjski, 31 villages, 1582 households; Moravski, 39 villages, 1960 households.

Beogradski:

City of Belgrade: no data. Districts: Vračarski, 21 villages, 1907 households; Gročanski, 17 villages, 2164 households; Kolubarski, 32 villages, 2262 households; Posavski, 26 villages, 2031 households; Kosmajski, 26 villages, 2277 households.

Valjevski:

Town: Valjevo, 951 households. Districts: Kolubarski, no data; Posavski, town of Obrenovac, 346 households, 19 villages, 1432 households; Podgorski, 50 villages, 2546 households; Tamnavski, 53 villages, 3473 households.

Knjaževački:

Town: Knjaževac, no data. Districts: Timočkoknjaževački, 67 villages, 4802 households; Svrljiški, 36 villages, 1954 households.

Jagodinski:

Town: Jagodina, 1058 households. Districts: Levački, 48 villages, 3367 households; Temnićki, 43 villages, 5457 households; Belički, census book is dameged, data are readable for about 10 villages.

Kragujevački:

Town: Kragujevac, no data. Districts: Jasenički, 22 villages, 2929 households; Lepenički, 37 villages, 4480 households; Kragujevački, 51 villages, 3503 households; Gružanski, 57 villages, 4231 households.

Krajinski:

Town: Negotin, 1155 households. Districts: Ključki, 20 villages, 2499 households; Porečkorečki, town of Majdanpek, 379 households, 10 villages, 1476 households; Brzoplanački, 21 villages, 3910 households; Krajinski, 26 villages, 4352 households.

Kruševački:

Town: Kruševac, 859 households. Districts: Jošanički, 42 villages, 1396 households; Trstenički, 36 villages, 2456 households; Kruševački, no data; Koznički, no data.

Podrinski:

Town: Loznica, 599 households. Districts: Jadarski, no data; Radjevski, 9 villages, 1824 households; Azbukovački, 20 villages, 2014 households.

Požarevački:

Town: Požarevac, 1891 households. Districts: Golubački, 29 villages, 2010 households; Zviždski, no data; Homoljski, no data; Ramski, town of Gradište, 718 households, 34 villages, 3469 households; Moravski, 44 villages, 6183 households; Mlavski, 38 villages, 5778 households.

Rudnički:

Town: Gornji Milanovac, 314 households. Districts: Kačerski, 34 villages, 2039 households; Moravski, 38 villages, 3589 households; Crnogorski, 38 villages, 2347 households.

Smederevski:

Town: Smederevo, 1272 households. Districts: Podunavski, 28 villages, 3906 households; Jasenički, 25 villages, 4957 households.

Užički:

Town: Užice, no data. Districts: Crnogorski, 38 villages, 2546 households; Račanski, 29 villages, 2102 households; Požeški, 36 villages, 2386 households; Zlatiborski, 24 villages, 2488 households; Ariljski, 26 villages, 1955 households; Moravički, 31 villages, 2465 households.

Crnorečki:

Town: Zaječar, 898 households. Districts: Boljevački, 21 villages, 3491 households; Zaječarski, census book is damaged, data are readable for 7 villages with 1408 households.

Čačanski:

Town: Čačak, 754 households. Districts: Trnavski, 27 villages, 1730 households; Dragačevski, 43 villages, 3367 households; Karanovački, town of Karanovac, 552 households, 39 villages, 2917 households; Studenički, 31 villages, 1483 households.

Ćuprijski:

Towns: Ćuprija, 564 households; Svilajnac, 966 households. Districts: Resavski, 53 villages, 4588 households; Paraćinski, 39 villages, 2984 households.

Šabački:

Town: Šabac, 2009 households. Districts: Mačvanski, 26 villages, 3975 households; Pocerski, 30 villages, 2738 households; Posavotamnavski, 54 villages, 2722 households.

Published 1862/63 census microdata

Towns

Valjevo: Branko Peruničić, Grad Valjevo i njegovo upravno područje 1815–1915, Valjevo 1973, 820–889.

Požarevac, Majdanpek, Veliko Gradište: Branko Peruničić, Grad Požarevac i njegovo upravno područje, Beograd 1977, 1477–1500 (Majdanpek), 1500–1557 (Veliko Gradište), 1558– 1693 (Požarevac).

Kruševac: Branko Peruničić, Kruševac u jednom veku 1815–1915, Kruševac 1971, 685– 753.

Aleksinac: Branko Peruničić, Aleksinac i okolina, Beograd 1978, 1026–1119.

Čačak: Branko Peruničić, Čačak i Gornji Milanovac, knj. II, Beograd 1968, 9–62.

Jagodina: Branko Peruničić, Grad Svetozarevo 1806-1915, Beograd 1975, 913–997.

Karanovac: Branko Peruničić, Jedno stoleće Kraljeva 1815-1915, Kraljevo 1966, 231– 276.

Šabac: Branko Peruničić, „Popis žitelja i njihove imovine u Šapcu 1862. godine“, Godišnjak Istorijskog arhiva u Šapcu, IV (1967) 255–336; V (1967), 233–348.

Loznica: „Popis žitelja Loznice 1862. godine“, priredila Mirjana Adamović, Godišnjak Medjuopštinskog istorijskog arhiva, XIV, Šabac 1980, 123–198.

Smederevo: Leontije Pavlović, Smederevo u 19. veku. Zanimanja, imovina i zarada stanovnika prema popisima 1833. i 1862–63. godine. Arhivski podaci sa komentarima, Smederevo 1969, 156–262.

Branko Peruničić, Naselje i grad Smederevo, Smederevo 1976, 997-1085.

Zaječar: Popis stanovnika varoši Zaječar iz 1863. godine, priredio Bora Dimitrijević, Zaječar 2000.

Negotin: Božidar Blagojević, Popis stanovništva i imovine varoši Negotin iz 1863,Negotin 2011.

Districts

Mlavski: Branko Peruničić, Petrovac na Mlavi, Beograd 1980, 465–1280.

Jasenički: Branko Peruničić, Popis stanovništva u srezu Jaseničkom 1863, Smederevska Palanka 1978.

Paraćinski: Branko Peruničić, Popis stanovništva i poljoprivrede u srezu Paraćinskom, Paraćin 1977.

Resavski: Branko Peruničić, Državni popis u Gornjoj Resavi 1863, Despotovac 1990.

Mačvanski: Milivoje Vasiljević, Mačva. Istorija, stanovništvo, Beograd 1996.

Ključki: Božidar Blagojević, Popis stanovništva i imovine sreza Ključkog, Negotin 2005.

Krajinski: Stanovništvo u Krajinskom srezu prema popisu iz 1863, priredio Nenad Vojinović, Negotin 2009.

Brzopalanački: Popis stanovništva i imovine sreza Brzopalanačkog, priredio Nenad Vojinović, Negotin 211.

Račanski: Milorad D. Bogdanović, Stanovništvo Račanskog sreza 1863, Bajina Bašta 2004.

Stamenko A. Stamenić, Popis žitelja Račanskog kraja 1863, Bajina Bašta-Užice 2004.

Azbukovački: Stamenko A. Stamenić, Azbukovica u popisu 1863, Bajina Bašta- Ljubovija-Valjevo 2005.

Rudnički: Državni popis stanovništva 1862/63. godine. Opština Gornji Milanovac, priredila Ana Stolić, Gornji Milanovac 1997.

Municipalities

„Popis žitelja i njihove imovine na području opštine Majdanpek 1863. godine“, priredio Vitomir Vasilić, Izvornik. Građa Međuopštinskog istorijskog arhiva 5 (1988), 27–54.

„Popis žitelja i njihove imovine na području opštine Ježevičke 1863. godine“, priredio Vitomir Vasilić, Izvornik. Građa Međuopštinskog istorijskog arhiva 6 (1989), 83–115.

„Popis žitelja i njihove imovine a području opštine ljubićke 1863. godine“, priredio Vitomir Vasilić, Izvornik. Građa Međuopštinskog istorijskog arhiva 7 (1990), 79–94.

„Popis žitelja i njihove imovine na području opštine goračke 1863. godine“, priredio: Zoran Marinković, Izvornik. Građa Međuopštinskog istorijskog arhiva 8 (1991), 88–112.

„Žitelji Brđana i Sokolića i njihova imovina 1863. godine“, priredio Milomir V. Glišić, Izvornik. Građa Međuopštinskog istorijskog arhiva 10 (1995), 35–53.

„Popis žitelja i njihove imovine na području opštine Brusničke 1863. godine“, priredila Zorica Matijević, Izvornik. Građa Međuopštinskog istorijskog arhiva 11 (1995), 43–57.

Popis stanovništva i poljoprivrede u selima opštine Mladenovac 1863, priredio Miladin V. Arsić, Mladenovac, Beograd 1990.

„Popis stanovništva i imovine varošice Donji Milanovac srez Porečko rečki iz 1863. godine“, priredio Velimir D. Šešum, Beograd 2002.

Ljubodrag Popović, „Naši stari. Popisi stanovništva na teritoriji današnje opštine Vrnjačka Banja 1834–1916“, Vrnjačka Banja 2002.

Censuses from 1866 to 1900

The census of 1866 is often mentioned as the first modern census in Serbia. It was conducted following the rules and forms created in the newly established statistical office. The census was performed simultaneously in the entire country, at the end of 1866. Belgrade was the only place where it was not performed properly, so it had to be performed again in early 1867. This time, the census was conducted in one day by sixty census takers. This was the first census which recorded literacy, nationality and citizenship. For the first time people were registered by the place where they were at the moment of census-taking, and not by their permanent residence. Furthermore, this was the first census the results of which were extensively published in statistical publications.

The census of 1874, conducted in December that year, was performed under the same principles as the previous one. Unlike the earlier censuses, it included the inquiry about denomination.[11] Following the recommendation of the International Statistical Congress, the next census was planned for the end of 1880. However, the census was postponed for four years due to the wars fought against the Ottoman Empire from 1876 to 1878. In the meanwhile, in 1879, a census was performed in four counties annexed to Serbia in the previous year. On that occasion the same census forms were used as in the 1874 census. Statisticians were not satisfied with the obtained results; they believed the census was poorly performed as census takers were not properly trained.

The next census which included the entire population took place in 1884, immediately after the first Law on Population and Property Census was passed. As in 1862, the main goal of this census was the introduction of a new tax system, based on wealth and income. Unlike the 1862/63 census, information on population and property was recorded in separate census protocols.

A special committee made the census rules and forms based on recommendations given at the statistical congress in St. Petersburg in 1872. The census itself was performed by a committee appointed by the Minister of Finance. One or more committees were appointed for each town of a county and each district so that the census would be performed in the shortest period of time. Since property had to be registered as well, the census lasted longer than expected and it was finished in March of the following year. Property registration raised some controversy as in 1862 (Jovanović 1927: 216) but, this time, tax reform was finally conducted.

New inquires in this census were about the mother tongue and the country and place of birth. The census of 1884 is the last one conducted in the 19th century from which some microdata have been preserved.

The subsequent censuses were performed according to the Law on Census-Taking which was passed in 1890 and partially amended in 1900. They were taken every five years – in 1890, 1895, 1900, 1905 and 1910. The established census cycle was broken by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The main information about these censuses are extensive aggregate data published within several statistical volumes.

1884 Census form: number/ordinal/of book listing fixed assessments; given and family name of head of family and other inmates with kinship relation; occupation; age/males/females; marital status/males married/widowed or divorced/females married/widowed or divorced; literacy/males/females; country and place of birth; citizenship; religion; mother tongue; disabled persons/blind/deaf-mute/mentally ill; remarks.

Published aggregate data:

1866 Census: „Popis ljudstva Srbije u godini 1866“, Državopis Srbije III (1869), 47–111.

„Popis ljudstva Srbije u godini 1866. po zanimanju“, Državopis Srbije XII (1883), 1–175.

„Skrižali popisa ljudstva u godini 1866. po zanimanju“, Državopis Srbije XIII (1884), 33– 413.

1874 Census: „Popis ljudstva Srbije u godini 1874-oj“, Državopis Srbije IX (1879), 1– 153.

1879 Census: „Popis ljudstva Srbije u oslobodjenim krajevima“, Državopis Srbije XI (1882), 1–57.

1884 Census: „Popis ljudstva u Kraljevini Srbiji 1884. godine“, Državopis Srbije XVI (1889), 1–273.

1890 Census: Prethodni rezultati popisa stanovništva i domaće stoke u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1890. godine, Beograd: Uprava državne statisitike 1891.

„Popis stanovništva u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1890. godine“, Statistika Kraljevine Srbije, vol. I-IV, Beograd 1892-1893.

1895 Census: Prethodni rezultati popisa stanovništva i domaće stoke u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1895. godine, Beograd: Uprava državne statisitike 1896.

„Popis stanovništva u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1895. godine“ Statistika Kraljevine Srbije, vol. XII-XIII, Beograd 1898.

1900 Census: Prethodni rezultati popisa stanovništva i domaće stoke u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1900. godine, Beograd: Uprava državne statisitike 1901.

„Popis stanovništva u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1900. godine“, Statistika Kraljevine Srbije, vol. XXIII-XXIV, Beograd 1903-1905.

1905 Census: Prethodni rezultati popisa stanovništva i domaće stoke u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1905, Beograd: Uprava državne statisitike 1906.

1910 Census: Prethodni rezultati popisa stanovništva i domaće stoke u Kraljevini Srbiji 31. decembra 1910, Beograd: Uprava državne statisitike 1911.

Preserved 1884 census microdata:

County, district

Aleksinački okrug, Aleksinački srez: town of Aleksinac, 1164 households.

Beogradski okrug, Gročanski srez: municipality of Ripanj, 444 households.

Kragujevački okrug, Jasenički srez: 28 villages, 3685 households.

Krajinski okrug, Ključki srez: 7 villages, 831 households.

Kruševački okrug, Kruševački srez: town of Kruševac, 567 households (out of 1217 households).

Smederevski okrug, Podunavski srez: 13 villages, 1745 households.

Ćuprijski okrug, Paraćinski srez: 21 villages, 1888 households. Ćuprijski okrug, town of Ćuprija: 850 households.

Čačanski okrug, Studenički srez: 2 villages (incomplete), 77 households.

Niški okrug, Leskovački srez: 49 villages, 2486 households.

Toplički okrug, Prokupački srez: 86 villages, 3464 households.

Repository

The preserved census microdata are kept nowadays in the Archives of Serbia/ Karnegijeva

2, 11000 Belgrade; phone: +381 11 3370 781; e-mail: [email protected]. All the data are

available on microfilms and can be scanned.

REFERENCES:

Cvijetić, Leposava. 1984. “Popis stanovništva i imovine u Srbiji 1834. godine“. Miscellanea (Mešovita gradja), 13: 9–118.

Đurđev, Branislav, Lukić, Tamara, Cvetanović, Milan. 2012. “Household Composition and the Well-Being of Rural Serbia in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century”, Journal of Family History 37: 55–67.

Gruber, Siegfried. 1999. The development of family and household structures in Serbia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries” in: Between the Archives and the Field: A Dialogue on Historical Anthropology of the Balkans. Belgrade-Graz: 47–68.

Gruber, Siegfried. 2011. “Der Mehrfamilienhaushalt in Serbien in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts” in: L. Breneselovic, (ed.): Spomenica Valtazara Bogišića: o stogodišnjici njegove smrti, 24. apr. 2008. godine. Knj. 2, Beograd: Službeni glasnik: 295–311.

Gruber, Siegfried, Szołtysek, Mikołaj. 2012. “Stem Families, Joint Families, and the European Pattern: What Kind of a Reconsideration Do We Need?”, Journal of Family History 37: 105–125.

Halpern, Joel M. 1958. A Serbian Village. New York: Columbia University Press.

Halpern, Joel M. 1972. “Town and countryside in Serbia in the nineteenth century: social and household structure as reflected in the census of 1863”, in: Peter Laslett and Richard Wall (eds.), Household and Family in Past Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 401–427.

Halpern, Joel M, Wagner, Richard A. 1981-1982. “Demographical and Social Change in the Village of Orašac. A Perspective over Two Centuries” in: Serbian Studies, vol. 1 (1981): 51– 70; vol. 1/4 (1982): 65–92; vol. 2/1 (1982): 33–60.

Halpern, Joel M, Wagner, Richard A. 1984. “A Microstudy of Social Process. The Historical Demography of a Serbian Village Community 1775 1975“, in: Kat K. Shangriladze (ed.), Papers for the Fifth Congress of Southeast European Studies. Ohio: 199–216.

Hammel, Eugene A. 1972. “The zadruga as process”, in: Peter Laslett and Richard Wall (eds.), Household and Family in Past Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 335– 373.

Hammel, Eugene A. 1976. “Some Medieval Evidence on the Zadruga: A Preliminary Analysis of the chrysobulls of Dečani” in: Robert F. Byrnes (ed.), Communal Families in the Balkans: The zadruga, Notre dame 1976: 100–116.

Jovanović, Slobodan. 1923. Druga vlada Miloša i Mihaila (1858–1868). Beograd: Izdavačka knjižarnica Gece Kona.

Jovanović, Slobodan. 1927. Vlada Milana Obrenovića. Knjiga druga (1878–1889). Beograd: Izdavačka knjižarnica Gece Kona.

Kaćanski, Gordana. 2001. “Kućne zajednice u deset sela u okolini Beograda 1832. godine”, Godišnjak za društvenu istoriju VIII, 1-2: 31–44.

Kaser, Karl. 1994. “The Balkan Joint Family”, Continuity and Change, vol. 9/1: 45–68.

Kaser, Karl. 1995. Familie und Verwandtschaft auf dem Balkan. Wien-Köln-Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Katić, Bojana. 1986. “Društvena struktura stanovništva Šapca 1862. godine”, Istorijski časopis XXXIII: 203–221.

Katić, Bojana. 1988. “Struktura stanovništva Velikog Gradišta i Majdanpeka”, Istorijski časopis XXXV: 119–132.

Katić, Bojana. 1990. ”Demografska i socijalna struktura varošica u Srbiji sredinom XIX vijeka”, Arhivski pregled 1–2: 69–73.

Katić, Bojana. 1991. “Les petites villes en Srbie: structure démographique et sociale vers le milieu du ХIХe siècle”, Le culture urbaine des Balkans (XV–XIX siècles), 3: La ville dans les Balkans depuis la fin du Moyen Age jusquau debut du XX siècle, Belgrade, Paris: Academie Serbe des Sciences et des Arts, Institut des balkaniques: 223–229.

Katić, Bojana. 1994. “Stanovništvo Valjeva 1862. godine”, Valjevo, postanak i razvitak gradskog središta.Valjevo: 265–278.

Miljković-Katić, Bojana. 2002. Struktura gradskog stanovništva Srbije sredinom XIX veka. Beograd: Istorijski institut, Službeni glasnik.

Miljković-Katić, Bojana. 2002. „Društvena struktura stanovništva Negotina sredinom XIX veka“, Baštinik. Godišnjak Istorijskog arhiva u Negotinu 5: 88–103.

Miljković-Katić, Bojana. 2003. “Rasprostranjenost zadruge u Krajinskoj kapetaniji u vreme prve vladavine kneza Miloša Obrenovića”, Baštinik. Godišnjak Istroijskog arhiva u Negotinu 6: 179–191.

Palairet, Michael. 1995. “Rural Serbia in the Light of the Census of 1863”, Journal of European Economic History 24: 41–107.

Porter, Theodore M. 1986. The Rise of Statistical Thinking, 1820–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stojančević, Vidosava. 1995. Porodica u Podgorini. U procesu formiranja tipova naselja i tradicionalnih sistema društvenih komunikacija (do kraja XIX i početka XX veka). Valjevo: Istorijski arhiv Valjevo.

“Svečani sastanak Srpskoga učenog društva radi proslave 50-godišnjice književnog rada g. Vladimira Jakšića“.1890. Glasnik SUD 71: 292–325.

Vuletić, Aleksandra. 2002. Porodica u Srbiji sredinom 19. veka. Beograd: Istorijski institut, Službeni glasnik.

Vuletić, Aleksandra. 2003. “Struktura seoske porodice u Ključu sredinom 19. veka”, Baštinik. Godišnjak Istorijskog arhiva u Negotinu 6: 192–199.

NOTES:

[1] Some literature mentions censuses allegedly conducted in 1837 and 1839. However, in most of the relevant literature (series of “Državopis Srbije”) there are no indications of these censuses. Only tax lists from the above mentioned years can be found in archival sources, but they do not contain the elements of a census [2] Along with the Serbian title of the edition, there was a French title as well (Statistique de la Serbie). Many tabulations within the edition were equipped with column headings in both languagues, Serbian and French. [3] The volumes of these editions containing extracts and analyses of census data will be mentioned in the second part of this paper [4] For more about his work, see: “Svečani sastanak…”, Glasnik SUD 71: 292-325. [5] In 1882 the authority over the National Statistics Office was transferred from the Ministry of Finance to the Ministry of Economy. The procedures for censuses taken from 1890 were described in detail in prefaces to the corresponding statistical volumes. See, for example: “Prethodni rezultati popisa…” 1911: V-VII [6] Ibid., p. VII. [7] The Turkish civilian population, which lived almost exclusively in urban areas, started to emigrate from Serbia after it was granted the autonomous status in 1830. In 1862, all remaining Turkish civilians were to leave Serbia. According to some estimations, about 3000 Turks left Belgrade that year („Državopis Srbije“ II: 15). Turkish military garrisons stationed in six towns were also to leave in 1867. [8] The survey was discovered, then edited and published by Leposava Cvijetić. All information about census-taking in 1834 is derived from the preface to that edition (Cvijetić 1984: 9-20). [9] In fact, these lists do not contain the years of census-taking. Dating was done by the archivists, according to some features of the lists. [10] See, for example: „Državopis Srbije“ I: 86-87. [11] Some of the extracts from previous censuses also contained information about the denomination, derived from other data (the name, nationality etc.). The census entry for denomination was introduced only in 1874.SOURCE: Vuletić, Aleksandra: “Censuses in 19th century Serbia: inventory of preserved microdata”, MPIDR WORKING PAPER WP 2012-018, Max-Planck-Institut für demografische Forschung / Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock (Germany), 2012

Web link: https://www.demogr.mpg.de/papers/working/wp-2012-018.pdf

Коментари (0)